Introduction

Philosophers often stroll and talk on outdoor porches. Socrates loved to do this and so did Aristotle, as well as Seneca, the Roman philosopher. In fact, he told his peers that we should "get out of the house and take walks to nourish our minds".

Walking has long been a method of thinking, problem-solving, and clearing the mind of chaotic, tangled thoughts. What is behind all this and how can we use walking to achieve cognitive excellence to work more efficiently and gain an edge in an increasingly fast-paced technological world?

As a physician with a neuroscience background, I have always been interested in how we can get the brain to work optimally. Today, as the Founder and CEO of Walkolution, a startup company that revolutionizes workplaces all over the world with treadmill desks, the topic couldn't be more important and fascinating to me.

Spontaneous fluctuations - the dark matter within our brains

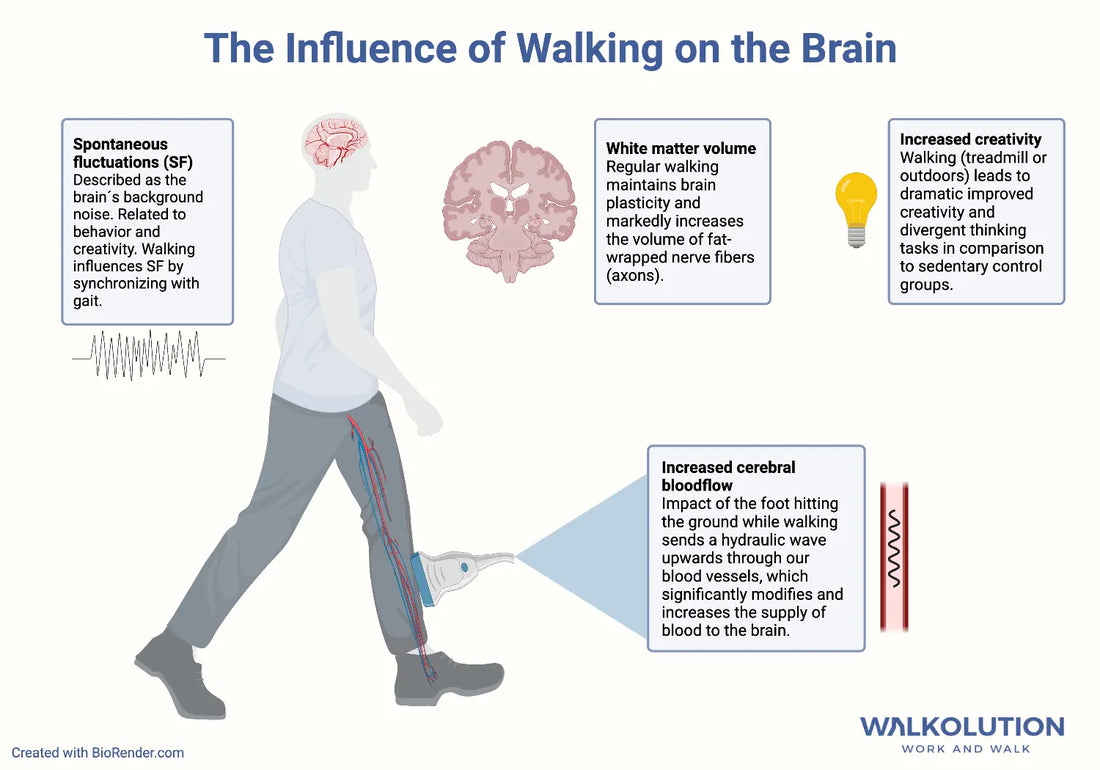

On a stroll, a lot happens to our bodies and minds, but one thing sticks out as particularly intriguing. They're all linked to an increase in "spontaneous cognitive fluctuations," as neuroscientists describe it.

This background noise of our brains was considered to be random and unimportant for almost a century, but increasing evidence shows that this is not the case. Cognitive fluctuations that happen while walking or during aerobic exercise are incredibly related to creativity and behavior.

Rather than being random noise, spontaneous oscillations are linked to established anatomical systems and are found in functionally connected brain regions. Non-neuronal elements such as heart or respiratory activity could be isolated and are not responsible for the observed association patterns.

During every moment of every day, our brains are working hard. We are constantly firing billions of neurons in our brains, even when we're lying in bed doing nothing but thinking about nothing at all. And doing nothing at all, might even be the key to unleashing hidden cognitive potential - interestingly, walking somehow brings us closer to that state of mind.

When body and mind are synchronizing, the mind can begin to wander, or as Henry David Thoreau said in his famous quote: "Methinks that the moment my legs begin to move my thoughts begin to flow."

Working while walking - only for multitaskers?

First of all, we must clearly distinguish that the ability of our brain to perform other things during movement is quite significantly depending on the complexity of the movement performed and the effort it causes.

In plain language, this means that while walking slowly, you can easily perform demanding intellectual tasks, whereas, during a performance of ballet choreography, you will not be able to do so that easily.

Admittedly, is an advanced brain exercise to walk with all the harmonious coordination between all the joints, bones, and muscles, and it requires multiple brain functions for all of this to happen simultaneously. But can the brain do even more? A current study from 2022 (1) indicates that this might be the case.

Researchers at the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience in Rochester, New York have learned that healthy brains can multitask while walking without negatively affecting how well you perform either task.

The virtual reality platform, 'Mobile Brain/Body Imaging', helped the team record 16 high-speed cameras at millimeter precision. They used this platform to record the position markers with precision while simultaneously measuring the brain activity of the participants. The participants walked on a treadmill and/or manipulated objects on a table while the cameras recorded their position with high accuracy.

The study has been published in the 'NeuroImage Journal'. The researchers found that the participants were even able to improve their walking pattern while multitasking, suggesting that their brain activity remained more stable when they were walking and performing other tasks simultaneously, contradicting previous beliefs.

Better circulation. Walking increases cerebral blood flow.

The brain needs more oxygen when working harder because it consumes more energy. The brain is the body's single most energy-consuming organ, accounting for about 20% of the body's total energy expenditure, even when we rest.

New research (2) has shown that blood flow to the brain is not just provided by the heart. The researchers discovered that the impact of our foot hitting the ground while walking sends a hydraulic wave upwards through our blood vessels, which significantly modifies and increases the supply of blood to the brain.

Using ultrasound measurements of blood velocity waves and arterial diameters, the small study of 12 young adults presented at the annual Experimental Biology meeting determined the cerebral blood flow rates to both sides of the brain during either a rest period or continuous walking at 1 meter per second. They found that, despite the fact that normal walking produces a smaller pressure wave than running does, it increases blood flow to the brain even more.

What is unexpected, according to research author Earnest Greene, Ph.D., "is the length of time it took us to ultimately measure this evident hydraulic effect on cerebral blood flow." When we're going quickly, our heart rates (about 120 beats per minute) are in line with our stride speeds and foot impacts.

Not only does this study show that among different kinds of physical activity, walking can have an impact on cognitive performance, but it also has implications for how we treat and prevent decline of cognitive function. As we age, our brains naturally shrink and we lose cerebral blood volume. This loss is linked to age-related cognitive detoriation, such as memory problems, Alzheimer's disease, mental health problems and impaired brain function.

Walking changes the structure of the brain and improves cognitive function

Until the late 1990s most researchers believed that people were born with the brain cells they would ever have. Due to the advances in science, we can now see that our brains remain plastic throughout life. New brain cells are created throughout a lifetime.

Animal research suggests that rodents produced brain cells 3 or 4 times more often when they ran, while human studies showed that beginning a program of regular exercise leads to greater brain volume. In essence, the research shows that our brains retain lifelong plasticity and change as we do, including in response to how we exercise.

Most studies of brain plasticity generally focused on gray matter, though, which contains the celebrated little gray cells, or neurons, that permit and create thoughts and memories. Less research has looked at the white matter, the brain's wiring. Made mostly of fat-wrapped nerve fibers known as axons, white matter connects neurons and is essential for brain health. But it can be fragile, thinning, and developing small lesions as we age, dilapidations that can be precursors of cognitive decline. It also has been considered relatively static, with little plasticity, or ability to adapt much as our lives change.

Agnieszka Burzynska, a professor of neuroscience and human development at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, suspected that science was underestimating white matter. She considered it likely that white matter possessed as much plasticity as its gray counterpart and could refashion itself, especially if people began to move.

In their study, they tested almost 250 older men and women who were in good physical health and had good aerobic fitness. At baseline, all subjects underwent an MRI to determine white matter volume. This examination was repeated at the end of the six-month study period. The group was then divided into 3 groups and trained three times a week for a total of six months with either stretching and balance training, brisk walking three times a week or dancing and group choreography classes in the third study group.

They expected that the brain changes would be seen more in the control group who were dancing because of the increased amounts of learning and practice. To the researcher's surprise, they found that walking had the greatest effects on white matter volume.

White matter is important for the brain´s overall health because it helps in the communication between different parts of the brain. The white color comes from the fatty sheath that surrounds each axon. This sheath helps speed up the messages as they travel from one part of the brain to another. Damages to these structures slow down or completely stop the messages from traveling between different brain centers as it occurs in various forms of dementia and neurodegenerative diseases. Walking seems to provide some protection against this decline.

The Stanford "walking and creativity" study

Stories about Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg’s walking meetings are often cited to back their claim that walking boosts creative inspiration.

Walking benefits creativity by improving divergent thinking and generating creative ideas. Highly focused tasks like resolving a mathematical equation are likely not to get solved with walking, but after recharging, individuals may be able to focus better afterward.

Allen Braun, a researcher at WRAIR, talks about how de-focused attention, which seems like an oxymoron, could actually be helpful for creativity. Braun says that 'we think what we see is a relaxation of executive functions to allow more natural de-focused attention and uncensored processes to occur that might be the hallmark of creativity.' He presents an argument that this is due to the fact that when walking, the brain is distracted enough to allow for a free flow of sources from the subconscious mind.

The brain functions better when relaxed, but it can be hard to relax. When people get really relaxed, they think more abstractly and more about the big picture.

Stanford researchers investigated this problem in a famous study (4) and found that creative thinking is better when walking and shortly thereafter. They examined the effects of walking on people and found that the number of creative thoughts increased by an average of 60%.

In their study, creativity levels were consistently and significantly higher for people who walked compared to those sitting. The experiment involved creativity tests for study participants who had to think of alternate uses for given objects. They were given several sets of three objects and had 4 minutes to come up with as many responses as possible. Responses were considered novel if no other participant in the group used them. In three experiments that were conducted with a total of 402 participants, the overwhelming majority of the participants found themselves more creative while walking than sitting. The study in addition also whether it makes a difference whether the test persons walked on a treadmill or outside in the free nature. The act of walking itself, not the environment, was the decisive factor for the improved creativity.

Conclusion: Walking and brain health

Peak cognitive performance can be enhanced and facilitated through physical exercise, specifically by walking as we have seen. Not all mechanisms are well understood, but walking has been shown to improve oxygenation of the brain, put the brain in a creative state, and allow us to access subconscious thoughts that can be very valuable for sophisticated cognitive performance. All of this results in better brain health. By incorporating walking into your daily routine, you will achieve better mental clarity and focus.

If you are looking for premier solutions to reduce the sedentary time at your workplace, have a look at Walkolution´s treadmill desks.

About the Author

References

(1) Richardson, D. P., Foxe, J. J., Mazurek, K. A., Abraham, N., & Freedman, E. G. (2022). Neural markers of proactive and reactive cognitive control are altered during walking: A Mobile Brain-Body Imaging (MoBI) study. NeuroImage, 247, 118853.

(2) Garcia AM, Cognasi TR, Shrestha K, Greene ER. Acute effects of walking on human cerebral blood flow. Submitted to FASEB Experimental Biology 2016 San Diego.

(3) Colmenares, Andrea Mendez, et al. "White matter plasticity in healthy older adults: the effects of aerobic exercise." Neuroimage 239 (2021): 118305.

(4) Oppezzo, Marily, and Daniel L. Schwartz. "Give your ideas some legs: the positive effect of walking on creative thinking." Journal of experimental psychology: learning, memory, and cognition 40.4 (2014): 1142.