Part 1: Why is Sitting so Dangerous?

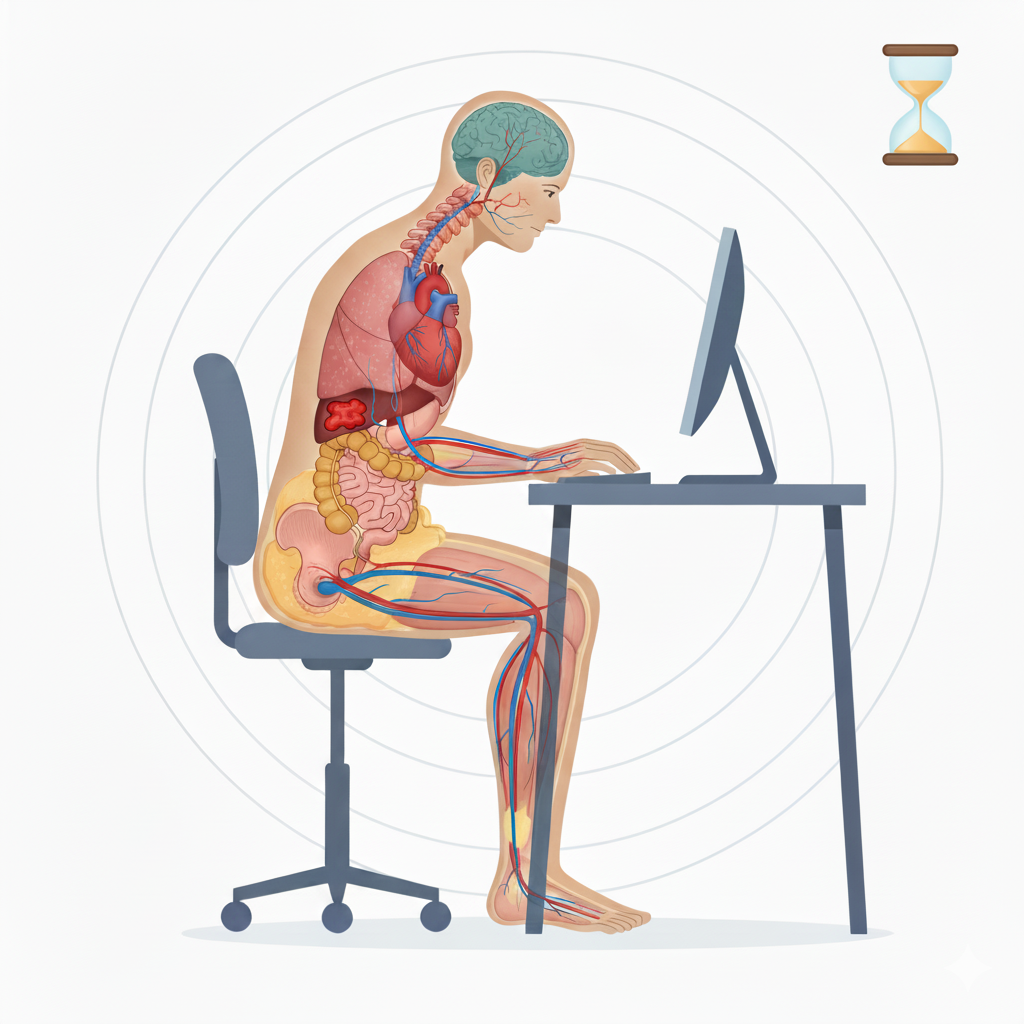

Modern work culture keeps us sitting for most of the day — often more than 10 hours. While sitting may seem harmless, decades of research have proven that prolonged sitting affects nearly every major organ system, increasing the risk of disease and premature death. Below is what happens inside the body when we sit for hours every day.

Sitting impairs blood sugar regulation and promotes insulin resistance, increasing diabetes risk. Chronic high blood sugar causes heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, nerve damage, blindness, and amputations. A sedentary lifestyle is a major driver of these metabolic health problems.

Prolonged sitting slows blood circulation, weakens the heart muscle, and increases blood pressure and inflammation. A sedentary lifestyle leads to more body fat and less muscle mass, raising harmful blood lipid levels. These changes significantly increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular disease. Sitting more than seven hours a day raises the risk of dying from heart disease by 85 %, and every additional two hours adds another 5 %. Long periods of sitting are a major but often overlooked threat to heart health.

Poor sitting posture compresses the lungs and diaphragm, reducing breathing capacity. This leads to shallow breathing and less oxygen intake. Over time, it causes chronic breathing impairment, lower energy, and impaired brain function. Concentration and memory suffer, and stroke risk increases. Sitting upright and moving regularly is essential for healthy breathing.

Sitting compresses the digestive tract, slowing digestion and causing inflammation. This harms the gut microbiome, disrupting healthy gut flora. Over time, it increases the risk of digestive disorders, allergies, asthma, metabolic syndrome, heart disease, and cancer. A sedentary lifestyle therefore impacts far more than posture—it affects core health systems.

Sitting disrupts dopamine and leptin, increasing hunger and promoting weight gain. This creates a vicious cycle where losing weight becomes harder. Obesity raises the risk of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, cancer, kidney and liver disease, and sleep and joint problems. Sitting too much is therefore a key driver of obesity and its serious health effects.

Sitting for over eight hours daily significantly raises the risk of lung, uterine, and colon cancer. Hormonal changes, excess insulin, chronic inflammation, and reduced antioxidant defenses contribute to this effect. Sitting more than eleven hours daily increases cancer mortality risk by 82 %. Prolonged sitting is therefore a major and preventable cancer risk factor.

Leaning the head forward while sitting strains the cervical spine, causing chronic tension and headaches. Over time, it can lead to spinal degeneration and herniated discs in the neck. Good posture and regular movement are essential to prevent these issues.

Sitting weakens the glutes, causing tightness, reduced mobility, and loss of stability. This raises the risk of falls, especially in older people. Constant compression damages nerves and tissues, sometimes irreversibly, leading to chronic pain and poor training response. Regular movement is crucial to maintain healthy glute function.

Sitting places enormous pressure on the spine, especially in the lumbar region, which significantly increases the risk of herniated discs. Over time, this leads to chronic back pain and degenerative changes in the spinal structures. The psychological burden of persistent pain is often high, and many patients end up being over-prescribed opioids.

Chronic lack of movement reduces neurotransmitter release, harming memory, mood, and focus. The brain shrinks without activity, raising the risk of depression, anxiety, dementia, and attention disorders. Sitting too much affects both mental performance and long-term brain health.

The comfort of the modern workday comes at a significant cost: our lifespan. Prolonged sitting has been strongly linked to an increased risk of premature death, regardless of regular exercise habits. A sedentary lifestyle affects multiple body systems — from the heart and metabolism to the brain and muscles — ultimately leading to a shorter life expectancy. Integrating regular movement into daily routines is one of the most effective ways to counteract this risk and support healthy longevity.

Cardiovascular System

Sitting slows blood flow and weakens the heart muscles, raising blood pressure and triggering chronic inflammation in blood vessels. This combination leads to higher levels of unhealthy fats in the blood and a significantly increased risk of heart attack and stroke. People who sit more than seven hours a day have an 85% higher risk of dying from cardiovascular disease, and the risk grows with every additional two hours spent seated. (1–6)

Respiratory System

A slumped posture at the desk reduces lung capacity by compressing the diaphragm between the torso and flexed hips. Over time, this chronic impairment lowers oxygen intake, decreases energy levels, and negatively affects brain function, including concentration and memory. (7–11)

Digestive System

Sitting compresses the abdomen, slowing digestion and promoting gut inflammation. This negatively impacts the gut microbiome and is associated with metabolic syndrome, heart disease, cancer, allergies, and asthma. Long periods of sitting after meals increase the risk of reflux and impaired nutrient absorption.(12–16)

Metabolism, Obesity & Diabetes

Inactivity disrupts the hormones leptin and dopamine, making it harder to regulate hunger and maintain a healthy weight. Prolonged sitting leads to insulin resistance and impaired glucose regulation, significantly increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes, stroke, kidney failure, and cardiovascular disease. Over time, this creates a vicious metabolic cycle that fuels further inactivity and weight gain. (1–6, 37–41).

Cancer Risk

Large cohort studies show that sitting more than eight hours daily raises the risk of lung cancer by 54%, uterine cancer by 66%, and colon cancer by 30%. Chronic inflammation, hormonal changes (e.g., IGF-1), and reduced antioxidant enzyme activity are contributing factors. People who sit more than 11 hours a day have an 82% higher risk of dying from cancer compared to those who sit less. (17–21)

Musculoskeletal System

Static sitting positions strain the cervical spine, causing chronic tension, headaches, and eventual disc degeneration. Gluteal muscles weaken through underuse, leading to instability, pain, and even permanent changes to muscles and fascia. Spinal discs are compressed, making sitting the main risk factor for herniated discs, chronic back pain, and spinal degeneration. (22–26)

Brain & Longevity

Physical movement stimulates neurotransmitters crucial for mood, memory, and cognitive function. Sitting reduces this stimulation, contributing to brain shrinkage, depression, anxiety, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. Prolonged sitting is also strongly linked to shortened life expectancy — even among those who exercise regularly. (1–6, 27–31).

Vascular Health & Leg Swelling

Extended sitting causes blood to pool in the lower limbs, raising venous pressure and oxidative stress. This leads to painful leg swelling, varicose veins, and an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). These vascular problems develop silently over time and can have life-threatening consequences if ignored. (32–36).

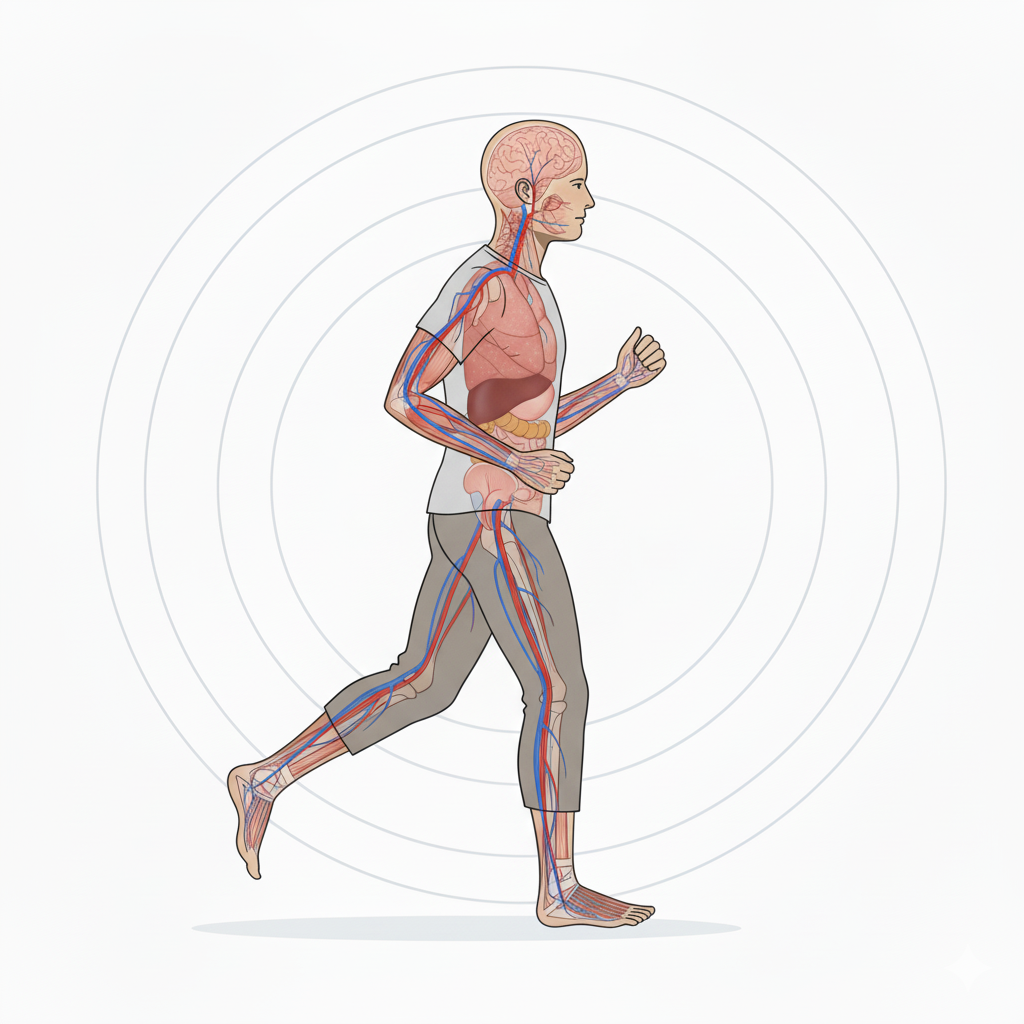

The Solution: Movement

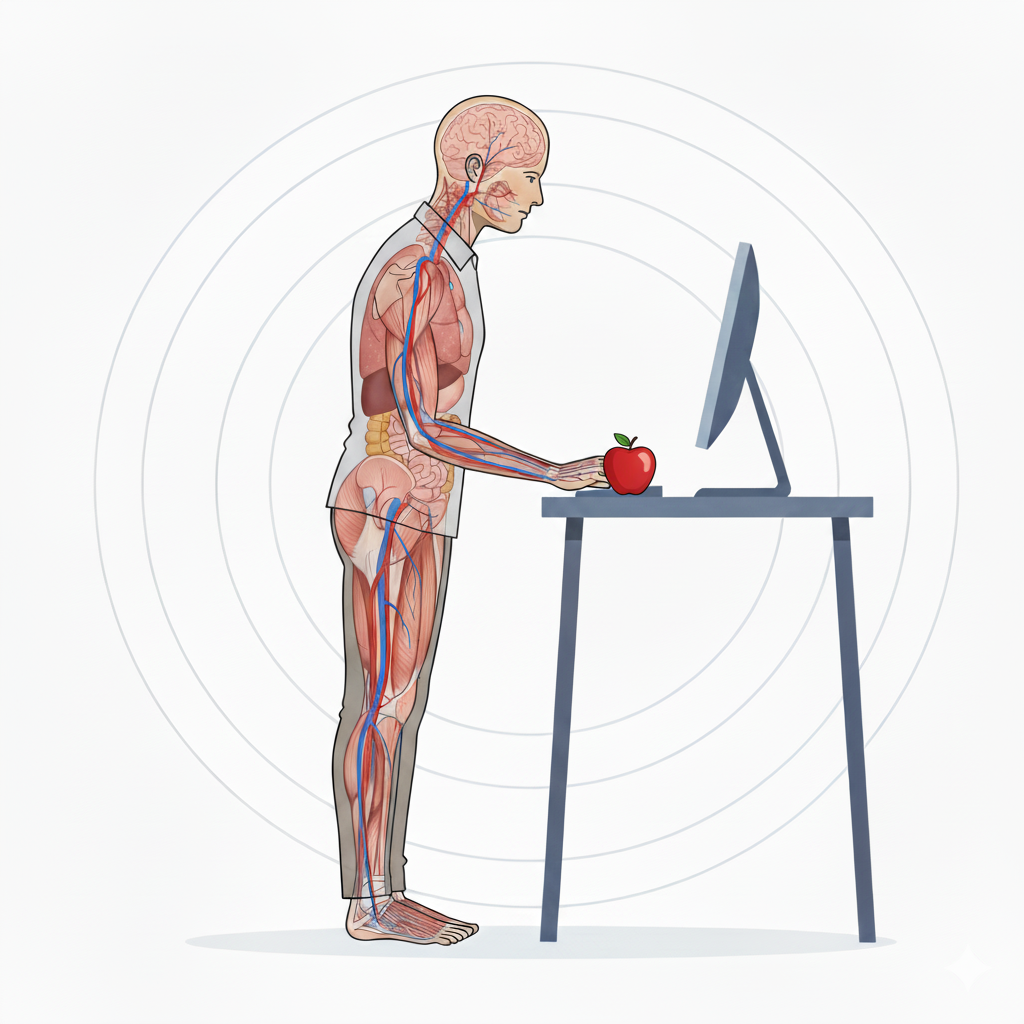

Neither sitting nor standing is healthy for extended periods. Regular movement — especially walking — is the only proven way to counteract the risks of sedentary behavior. Walking activates more than half of the body’s muscles, improves circulation, supports metabolic health, and boosts cognitive function. This is why Walkolution pioneered treadmill desks: to bring natural movement back into modern work life.

Standing Desks are not the solution

Switching between sitting and standing doesn’t address the core issue: lack of movement. Our bodies are designed to move, not to remain in static positions. Simply elevating the desk doesn’t counteract the negative health effects of prolonged inactivity. Standing desks offer a false sense of improvement without meaningful physiological benefits.

Standing burns only about 9 extra calories per hour compared to sitting. Over six hours, that equals roughly the calories in a single apple. In contrast, walking activates hundreds of muscles and burns around 400 calories per hour. Standing desks give the illusion of a healthier lifestyle but fail to support weight loss or significant metabolic improvement.

Prolonged standing often leads to slouching, leaning to one side, or excessive lumbar arching, especially in individuals with weak core or gluteal muscles from years of sitting. This posture can compress spinal discs and cause lower back pain. Standing desks frequently aggravate existing postural issues rather than correcting them.

Studies show that standing for just two hours at a workstation increases muscle fatigue, leg swelling, and discomfort. These physical effects are accompanied by a measurable decline in attention and reaction time. Instead of improving productivity, prolonged standing can make workers tired and mentally less sharp.

Despite widespread availability, most standing desks aren’t used as intended. Many users eventually revert to sitting because standing feels uncomfortable.

Contrary to popular belief, standing for long periods may increase the risk of heart disease. A Canadian study found that workers who stood most of the day had twice the risk of developing heart disease compared to those who sat. Prolonged standing leads to blood pooling in the legs and increased venous pressure, placing extra stress on blood vessels over time.

Standing for long periods causes blood to pool in the lower limbs, increasing venous pressure and oxidative stress in the vessels. This can lead to painful leg swelling, heaviness, and in the long run, elevate the risk of chronic venous insufficiency and even deep vein thrombosis (DVT). These vascular problems not only affect comfort but also carry significant health risks. Unlike walking, standing does not promote effective blood circulation.

Why Standing Desks Are Overrated: The Hidden Health Risks of Prolonged Standing

Standing desks have become one of the hottest workplace trends in recent years. Marketed as a healthy alternative to sitting, they’ve found their way into offices, home workspaces, and corporate wellness programs around the world. But beneath the sleek marketing lies a different reality: standing desks don’t solve the core problem of modern work — inactivity. (1–6, 22–26, 32–36)

A growing body of research reveals that standing desks often offer minimal benefits and can even introduce new health risks. Below, we break down the most important findings and explain why movement — not standing — is the real solution.

Standing Desks Don’t Solve the Sitting Problem

Switching between sitting and standing does not address the fundamental issue: lack of movement. Our bodies are not designed to remain static for hours on end. Simply elevating a desk fails to counteract the physiological effects of prolonged inactivity. Standing desks offer a false sense of improvement without meaningful health benefits.

Minimal Calorie Burn — The Weight Loss Myth

Many people use standing desks in the hope of burning more calories. The reality is underwhelming: standing burns only about 9 additional calories per hour compared to sitting. Over six hours, this equals the energy of roughly one apple. By contrast, walking activates hundreds of muscles and burns around 400 calories per hour. Standing desks are therefore not an effective weight management tool. (37–41)

Poor Posture and Musculoskeletal Strain

Standing for long periods often leads to slouching, leaning on one leg, or exaggerated lumbar curvature, particularly in people with weak core or gluteal muscles after years of sitting. This posture compresses the intervertebral discs and can cause lower back pain. Instead of correcting bad posture, standing desks often make it worse.(22–26)

Leg Swelling and Vascular Stress

Standing increases venous pressure in the lower limbs, leading to blood pooling, oxidative stress in the vessel walls, and inefficient circulation. The result is painful leg swelling, heaviness, and discomfort, which can appear after only a few hours of use. Over time, this can raise the risk of chronic venous insufficiency and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Unlike walking, standing does not activate the calf muscle pump that supports healthy circulation.(32–36)

Fatigue and Cognitive Decline

Scientific studies show that standing for just two hours at a computer workstation causes significant muscle fatigue, leg swelling, and discomfort. These physical effects are accompanied by a measurable decline in attention and reaction time. Rather than boosting productivity, prolonged standing can make workers tired and mentally less sharp. (22, 27–31, 32–36).

Low Adoption Rates in Real Workplaces

Despite their popularity, many users don’t stick with standing desks in the long term. Studies reveal that a large share of people revert to sitting because standing feels uncomfortable or fatiguing. On average, height-adjustable desks reduce total sitting time by only 30 minutes to two hours per day — far less than the dramatic claims often made in marketing. (1–6, 22–26, 32–36)

Increased Cardiovascular Risk

Surprisingly, prolonged standing may increase the risk of heart disease. A large Canadian cohort study found that workers who stood most of the day had twice the risk of developing heart disease compared to those who sat. The likely explanation is chronic vascular stress from blood pooling in the legs, which places strain on veins and arteries over time.(1–6, 32–36).

Movement Is the Only Real Solution

Neither sitting nor standing is healthy for extended periods. The only proven way to combat the negative effects of sedentary work is regular movement. Walking engages more than half of the body’s 650 muscles, boosts circulation, supports metabolism, and improves cognitive function. Treadmill desks and active workstations provide the dynamic activity that standing desks simply can’t replicate.

Exercise Can’t Undo the Damage of Sitting

Many believe that regular exercise can offset the risks of prolonged sitting. Modern science tells a different story: sedentary time and physical activity are two independent factors. Even if you exercise regularly, long hours spent sitting still harm your body — increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, metabolic disorders, and premature death.

Two Separate Risk Factors

Sitting and exercise act through different biological pathways.

Sedentary behavior suppresses muscular and metabolic activity for most of the day, while exercise only provides a short, temporary stimulus. This means that even if you work out in the morning or evening, the hours of inactivity in between still pose a serious health risk. (1–6)

Exercise Does Not Reverse Sitting-Induced Damage

Cardiovascular and metabolic harm from sitting continues, even in active individuals.

Large cohort studies (e.g., Matthews et al., 2015; Chau et al., 2015) show that prolonged sitting increases mortality risk independently of physical activity levels. People who exercise regularly but sit more than 8–10 hours a day still face a significantly higher risk of early death compared to active individuals who sit less. (1–6)

Muscles Need Continuous Activation

Short workouts cannot replace all-day low-intensity movement.

Sitting shuts down more than half of the body’s 650 muscles, especially in the legs and glutes. This reduces fat metabolism, increases insulin resistance, and decreases vascular activity. A one-hour gym session cannot counteract 10 hours of muscular inactivity at the desk.( 6, 37–41)

Why Movement Throughout the Day Matters

The human body is designed for continuous, low-intensity movement. Our muscles, blood vessels, and metabolism require frequent stimulation to function properly. Prolonged sitting causes insulin sensitivity to drop within hours, slows fat breakdown, and increases inflammation. No matter how intense your workout is, if you remain sedentary for the rest of the day, these harmful processes remain active. (1–6, 37–41)

The solution isn’t to give up exercise — it’s to integrate movement into your workday. Walking at a treadmill desk keeps muscles active, improves circulation, stabilizes metabolism, and protects long-term health. Movement must become part of your daily baseline, not just an add-on at the gym.

Sitting is the new Smoking

Further Reading

Death by Sitting. Why We Need A Movement Revolution explains clearly why the human body is so unsuited to sitting for long periods of time and what specific health risks are associated with a sedentary lifestyle. In addition, the book also illustrates how our cognitive performance and mental balance can be significantly improved through physical activity.

Major newspapers & magazines

The Wall Street Journal

- “The Price We Pay for Sitting Too Much.” WSJ, 2015. Wall Street Journal

- “Are Standing Desks Good For You? 8 Questions and Answers.” WSJ Buy Side, 2024. Wall Street Journal

- “How Bad Sitting Posture at Work Leads to Bad Standing Posture All the Time.” WSJ, 2014. Wall Street Journal

- “Want to Get More Done at the Office? Just Stand Up.” WSJ, 2016. Wall Street Journal

TIME Magazine

- “The War on Sitting / Sitting and Exercise hub.” TIME, (evergreen collection). TIME

- “Here’s a New Warning That Sitting Too Much Can Be Deadly.” TIME, 2016. TIME

The Guardian / The Times (UK)

- “Standing desks do not reduce risk of stroke and heart failure, study suggests.” The Guardian, 2024. The Guardian

- “Standing desks may increase risk of circulatory problems.” The Times, 2024. The Times

The Independent

- “Experts issue health warning to anyone who uses a standing desk.” The Independent, 2024. The Independent

Forbes / WIRED / Tech outlets

- “Prolonged Standing May Harm Your Health, New Study Reveals.” Forbes, 2025. Forbes

- “Ditch Your Office Chair for a New ‘Standing Desk’.” WIRED, 2012. WIRED

- “Experts issue a health warning over standing desks….” TechRadar, 2024. TechRadar

- “Study finds standing desks may be bad for your health.” TechSpot, 2024. TechSpot

- “Standing desks may not be the fix for heart health.” PCWorld, 2024. PCWorld

Harvard / Mayo Clinic

- “The dangers of sitting.” Harvard Health Publishing, 2019. Harvard Health

- “The truth behind standing desks.” Harvard Health Publishing, 2016. Harvard Health

- “What happens when you sit too much — and what to do about it.” Mayo Clinic Press, 2025. Mayo Clinic McPress

Recent medical-news

- “Study finds too much sitting hurts the heart.” Harvard Gazette, 2024. Harvard Gazette

- “JACC study: Sitting too long can harm heart health.” American College of Cardiology, 2024. American College of Cardiology

- “Too much sitting can still be harmful even if you exercise.” ScienceAlert on JACC study, 2024. ScienceAlert

Other Books

- Levine, J. A. (2014). Get Up!: Why Your Chair Is Killing You and What You Can Do About It. (Griffin/Macmillan). Proof/retail listings and library records: Amazon+1

- Vernikos, J. (2011). Sitting Kills, Moving Heals. (Quill Driver Books/Linden Publishing). Publisher sheet & retailer: joanvernikos.com+1

- Starrett, K., & Cordoza, G. (2016). Deskbound: Standing Up to a Sitting World. (Victory Belt). Publisher & retailer records: Victory Belt+2Amazon+2

- Bowman, K. (2015/2017). Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement. (Propriometrics Press). Library/retailer records: Google Bücher+2Amazon+2

References

Cardiovascular & Metabolic Health

1. Biswas, A., Oh, P.I., Faulkner, G.E., Bajaj, R.R., Silver, M.A., Mitchell, M.S. and Alter, D.A. (2015). Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(2), pp.123–132. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-1651

2. Ekelund, U. et al. (2019). Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: Systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ, 366, l4570. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4570

3. Chau, J.Y. et al. (2013). Daily sitting time and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e80000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080000

4. Matthews, C.E. et al. (2012). Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors and cause-specific mortality in US adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 95(2), pp.437–445. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.019620

5. Petersen, C.B. et al. (2014). Total sitting time and risk of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in a prospective cohort of Danish adults. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-13

6. van der Ploeg, H.P. et al. (2012). Sitting time and all-cause mortality risk in 222,497 Australian adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(6), pp.494–500. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.65

Respiratory System & Posture

7. Lin, F. et al. (2006). Effect of different sitting postures on lung capacity, expiratory flow, and lumbar lordosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87(4), pp.504–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.11.031

8. Makhsous, M. et al. (2003). Biomechanical effects of sitting with adjustable ischial and lumbar support on occupational low back pain. Spine, 28(11), pp.1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000065487.11496.F6

9. Katsuda, Y., Matsumura, T. and Nakano, H. (2020). Effect of forward head posture on pulmonary function in healthy adults: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 32(7), pp.480–483. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.32.480

10. Kose, M. and Ozturk, A. (2019). The relationship between thoracic kyphosis and respiratory function in sedentary office workers. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, 42(4), pp.E27–E33. https://doi.org/10.25011/cim.v42i4.32435

11. Lee, L.-J. et al. (2010). Changes in sitting posture can affect lung function in healthy adults. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 109(2), pp.313–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1359-0

Digestive System & Microbiome

12. Khor, B. et al. (2023). Physical inactivity is associated with reduced gut microbiome diversity and composition in office workers. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14, 1167893. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1167893

13. Estaki, M. et al. (2016). Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of intestinal microbial diversity and distinct metagenomic functions. Microbiome, 4, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0189-7

14. Allen, J.M. et al. (2018). Exercise alters gut microbiota composition and function in lean and obese humans. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 50(4), pp.747–757. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001495

15. Ticinesi, A. et al. (2017). Gut microbiota composition is associated with polypharmacy in elderly hospitalized patients. Scientific Reports, 7, 11102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10734-y

16. Batacan, R.B. et al. (2017). Effects of light intensity activity on CVD risk factors: A systematic review of intervention studies. Sports Medicine, 47(2), pp.213–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0552-8

Cancer

17. Hermelink, R. et al. (2022). Sedentary behavior – An umbrella review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology, 37(5), pp.447–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-022-00873-6

18. Schmid, D. and Leitzmann, M.F. (2014). Television viewing and time spent sedentary in relation to cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 106(7), dju098. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju098

19. Katzmarzyk, P.T. et al. (2023). Sitting time and cancer mortality: Results from the REGARDS Study. JAMA Oncology, 9(1), pp.12–14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36507079/

20. Keimling, M., Schmid, D. and Leitzmann, M.F. (2019). Sedentary behaviors and risk of cancer: A systematic review of the evidence. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 28(5), pp.849–854. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0527

21. Cong, Y.J. et al. (2014). Association of sedentary behaviour with colon and rectal cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. British Journal of Cancer, 110(3), pp.817–826. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.709

Musculoskeletal System

22. Baker, R. et al. (2018). The short-term musculoskeletal and cognitive effects of prolonged standing during office computer work. Ergonomics, 61(7), pp.877–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2017.1420811

23. Guilhem, G., Pauthier, A. and Rabita, G. (2020). Physical inactivity and intervertebral disc degeneration: MRI-based evidence in adults. European Spine Journal, 29(8), pp.1941–1950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06438-0

24. Heuch, I. et al. (2013). Physical activity level at work and risk of chronic low back pain: A follow-up in the HUNT Study. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e59105. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059105

25. Cifuentes, M. et al. (2010). Longitudinal associations of occupational sitting with musculoskeletal symptoms among U.S. workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 67(11), pp.724–728. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2009.050087

26. Kwon, Y. et al. (2015). The effect of sitting position on the lumbar spine motion and intervertebral disc pressure. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(6), pp.1699–1702. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.1699

Brain, Cognition & Longevity

27. Cai, X.-Y. et al. (2023). Association between sedentary behavior and risk of cognitive decline or mild cognitive impairment among the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1221990. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1221990

28. Falck, R.S., Davis, J.C. and Liu-Ambrose, T. (2017). What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(10), pp.800–811. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097415

29. Vance, D.E. et al. (2019). The association of sedentary behaviour and cognitive performance across cultures: A cross-national analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(5), pp.767–776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01186-7

30. Kremen, W.S. et al. (2010). Association of sedentary behavior with brain structure in middle-aged adults. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 4(2), pp.123–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-010-9091-0

31. Sedentary behavior and lifespan brain health. (2024). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. https://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/abstract/S1364-6613%2824%2900030-5

Vascular Health & Thrombosis

32. Kabrhel, C. et al. (2011). Physical inactivity and idiopathic pulmonary embolism among women: A prospective study. Circulation, 123(12), pp.1278–1285. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.963546

33. Healy, G.N. et al. (2008). Breaks in sedentary time: Beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes Care, 31(4), pp.661–666. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-2046

34. Thosar, S.S. et al. (2015). Effect of prolonged sitting and breaks in sitting time on endothelial function. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47(4), pp.843–849. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000479

35. Howard, B.J. et al. (2013). Impact on hemostatic parameters of interrupting sitting with short bouts of light-intensity walking. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 11(11), pp.2112–2114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12425

36. Scurr, J.H. et al. (2001). Frequency and prevention of symptomless deep-vein thrombosis in long-haul flights: A randomised trial. The Lancet, 357(9267), pp.1485–1489. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04645-6

Intervention / Movement Strategies

37. Dunstan, D.W. et al. (2012). Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes Care, 35(5), pp.976–983. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1931

38. Peddie, M.C. et al. (2013). Breaking prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glycemia in healthy, normal-weight adults: A randomized crossover trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 98(2), pp.358–366. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.051763

39. Bailey, D.P. et al. (2015). Changes in vascular function and posture during prolonged sitting: Influence of a sitting interruption protocol. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25(6), pp.749–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12393

40. Barone Gibbs, B. et al. (2015). Definition, measurement, and health risks associated with sedentary behavior. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47(6), pp.1295–1300. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000517

41. Levine, J.A. (2004). Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): Environment and biology. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 286(5), pp.E675–E685. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00562.2003

Part 2: Impact on Productivity,Concentration, and Creativity

Executive Summary

- Productivity: Using treadmill desks (walking at ~1–2 km/h) can slightly slow down certain tasks (e.g. typing speed drops by ~5–15% initially[1][2]). However, error rates generally remain low (no significant increase for walking desks[3]; cycling desks saw a small uptick in typos[2]). Crucially, long-term studies up to 1 year find no overall productivity loss once users adapt[4][5]. In fact, employees often report maintained or even improved work focus and efficiency after adjusting to walking workstations[6][7].

- Cognitive Performance: Attention and executive function are largely unaffected or slightly improved by slow treadmill walking. Controlled trials show no impairment in selective attention, processing speed, or working memory while walking vs. sitting[8][9]. Meta-analyses and RCTs report no overall cognitive deficits – any performance declines are due to motor coordination, not mental capacity[10]. Some studies even found enhanced cognitive control and memory after using a treadmill desk (a “post-walk” boost in recall and concentration)[11][12]. Thus, moderate walking during work can be introduced without harming concentration, aside from a slight dip in verbal memory during walking in some cases[13].

- Creativity: Walking is known to spark creative thinking – e.g. a Stanford study found walking (indoors or outdoors) significantly increased idea generation on divergent thinking tasks[14]. Treadmill desks can harness this effect for brainstorming; however, recent tests show no significant creativity improvement when performing creative tasks simultaneously with typing on a treadmill desk (no gains in Alternate Uses or Remote Associate Test scores at 1.5 mph vs. sitting[15]). The likely recommendation is to use walking breaks for inspiration (to “open up free flow of ideas”[16]), rather than expecting a boost while actively typing or coding on the move.

- Health & Engagement Benefits: Beyond the scope of direct performance, treadmill desks confer health advantages that can indirectly benefit productivity. Regular slow walking at work dramatically reduces sedentary time[17], raises daily physical activity (~+20–30% energy expenditure)[18], and can lead to modest weight loss and better metabolic markers (e.g. lower fasting glucose, improved HDL cholesterol)[19]. Users often report improved mood, higher energy, and less stress when integrating walking into their routine[7]. Over time, these benefits translate to better overall well-being and potentially fewer sick days, supporting a positive cost-benefit ratio. Notably, year-long trials concluded that introducing treadmill desks “was not associated with altered work performance”[4]—so companies can improve employee health without sacrificing output.

- Key Recommendations: Introduce treadmill desks gradually with training and ergonomic setup. Limit walking speed to ~1–2 km/h (≈0.6–1.2 mph) for knowledge work to ensure typing accuracy and reading comprehension stay high[3][20]. Encourage an adaptive period (e.g. start with 15–30 min intervals) so staff can acclimate to walking while working; evidence suggests initial performance dips diminish after a few weeks of practice[21][22]. Combine walking sessions with normal sitting/standing periods (e.g. 1–2 hours of walking spread across the day[20]) to minimize fatigue. Ensure treadmills (ideally quiet and stable) are set up with proper desk height and monitor alignment to maintain comfort and productivity. Electric vs. manual treadmills: Both can be effective; electric treadmills maintain a constant pace for consistency, whereas modern manual treadmills offer nearly silent operation and stop automatically when you step off (safety bonus). No research to date shows cognitive-performance differences between manual and motorized units, so factors like noise, maintenance, and user preference should guide selection. Overall, when implemented with these guidelines, treadmill desks can be a sustainable innovation that boosts worker wellness and may enhance certain aspects of focus and creativity, all while keeping productivity on track.

Authored by Eric Söhngen, M.D., Ph.D.

Affiliation & Disclosure

Dr. Eric Söhngen is the Founder and CEO of Walkolution GmbH (Germany), a manufacturer of

manual treadmill desks, and a board-certified medical doctor in General Internal Medicine. This

report was prepared independently and reflects the author’s professional assessment of the

evidence as of 15 October 2025.

Introduction & Background

Sedentary office work is a well-documented health risk, associated with obesity, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disorders[23][24]. Traditional desks confine workers to prolonged sitting, which not only harms physical health but can also lead to fatigue and reduced mental sharpness. Active workstations – including treadmill desks (a desk combined with a slow treadmill) – have emerged as interventions to break up sitting time and get workers gently moving. The appeal is a potential “win-win”: reduce sedentary behavior without sacrificing work effectiveness.

Treadmill desks allow an employee to walk at a gentle pace (typically ~1–2 km/h) while performing computer-based tasks. Early adopters claim benefits like higher energy and focus, but skeptics worry that walking might distract workers or slow them down. This report provides a comprehensive, evidence-based review of how walking at work (vs. sitting or standing) affects productivity, concentration, and creativity during common office tasks. We compare electric vs. self-powered treadmills and even other active workstations (like cycling desks), and we consider both short-term effects and longer-term adaptation. Key questions include:

- Does walking while working impact performance metrics (typing speed/accuracy, task completion time, error rates, etc.) compared to sitting or standing?

- How are cognitive functions like attention, working memory, and executive control influenced by treadmill work?

- Can walking enhance creative thinking, or does it interfere with complex idea generation?

- Do any initial performance impairments diminish over time with practice (learning curve effects)?

- What moderating factors (task complexity, fitness level, ergonomics, etc.) influence outcomes?

- Are there differences between electric vs. manual treadmill desks in user experience or performance impact (e.g. due to noise or friction)?

- How do treadmill desks compare with standing desks or desk bikes for both productivity and health outcomes?

- What side effects or risks should be considered (musculoskeletal strain, fatigue, safety concerns, noise distractions)?

To answer these, we draw on peer-reviewed studies (lab experiments, field trials, randomized crossover studies, longitudinal interventions) and credible industry reports. We include notable case studies such as medical professionals (radiologists) using treadmill desks while performing diagnostic tasks, to illustrate feasibility in high-stakes settings. The goal is to quantify benefits and drawbacks and distill practical guidance for decision-makers considering active workstations.

(Note: All evidence is up-to-date as of 15 October 2025, and key sources are cited for verification. The analysis encompasses research mainly from the last ~15 years, reflecting growing scholarly interest since the early 2010s when treadmill desks entered mainstream discourse.)

Methods Overview

Search Strategy: We conducted a systematic literature search in English and German across multiple databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and Google Scholar. Keywords included variations of “treadmill desk”, “walking workstation”, “active workstation” combined with terms like productivity, performance, accuracy, typing, attention, cognition, creativity, etc. (e.g. “treadmill OR walking desk” AND “productivity OR cognitive OR creativity”). Parallel German terms (e.g. “Laufband Schreibtisch Produktivität”) were used to capture any regional studies. We also scanned reference lists of relevant papers and included credible secondary sources (e.g. news articles or industry whitepapers) that cited data from studies.

Inclusion/Exclusion: We focused on studies that measured cognitive or work performance outcomes during desk work under different conditions (sitting vs. standing vs. walking). Included designs ranged from controlled lab studies and crossover trials to longitudinal workplace interventions and qualitative studies (for user perceptions). Both peer-reviewed articles and well-documented reports were included. We excluded purely physiological studies that lacked performance metrics (e.g. papers only measuring heart rate or calorie burn), as well as anecdotal blog posts or marketing materials without data. In total, we identified a core set of around 20–25 primary studies and several review/meta-analysis papers that met our criteria, encompassing data from hundreds of participants (from college students to office workers) in tasks from typing and reading to creative tests and image analysis.

Data Extraction & Quality: For each study, we noted the design, sample (including any relevant demographics like age or occupation), task types tested, conditions compared (speeds of walking, etc.), treadmill type (motorized vs. manual if stated), outcome measures, and main results (including effect sizes when reported). Key performance indicators included words per minute (WPM) typed, typing error rate, mouse pointing/clicking speed, task completion times, accuracy on cognitive tests or work tasks, and for creative tasks, scores on standard tests (Alternate Uses, Remote Associates). We also captured subjective outcomes (e.g. self-reported focus, NASA-TLX workload, discomfort) if reported. Each study’s risk of bias was qualitatively assessed (e.g. noting if it was randomized, if participants had acclimation time, etc.). Many short-term trials were within-subject designs (reducing inter-person variability), though not blindable due to the nature of intervention. Overall, the evidence base includes multiple systematic reviews[5] and at least two meta-analyses[25], lending confidence to general trends. However, sample sizes in individual experiments were often modest (10–40 people) and mostly short-term; this is reflected in cautious interpretations.

(A PRISMA-style flow diagram of study selection and detailed evidence tables by outcome are available in Appendix A of the full report. Key quantitative findings are synthesized below.)

Effects on Work Performance Metrics (Typing, Output, Errors)

One of the primary concerns for employers is whether walking will slow down employees or cause mistakes. Research consistently shows a small trade-off in raw performance speed when working on a treadmill desk, especially for tasks requiring fine motor skills or quick reactions. Importantly, accuracy tends to be preserved, and with practice these speed deficits can be minimized.

- Typing Speed: Nearly all studies find that typing while walking is a bit slower than sitting. A frequently cited early experiment had office workers type while sitting vs. walking ~1.6 km/h; typing speed dropped from about 40 WPM sitting to ~37 WPM walking (≈8% slower)[1]. A 2020 meta-analysis quantified this effect: treadmill desks led to a significant reduction in typing speed (standardized mean difference ~−0.8), meaning a notable slowdown compared to seated work[2]. By comparison, under-desk cycling caused a smaller drop (SMD ~−0.35)[2], likely because cycling involves less upper-body movement. It’s important to note these are initial effects; some of this is simply getting used to coordinating walking and typing.

- Typing Errors: Surprisingly, walking doesn’t seem to cause a typo epidemic. Studies typically report no significant difference in error rate between sitting and walking conditions. For instance, one trial showed transcription accuracy was unchanged (near 100% in both conditions) even though typing speed fell slightly on the treadmill[3]. The aforementioned meta-analysis did find a slight increase in errors with cycling desks (SMD ~+0.39)[2], but for treadmill desks the error increase was not statistically significant. In sum, people type a bit more slowly while walking, but maintain accuracy, perhaps by concentrating more on the task.

- Mousing and Click Tasks: Using a mouse or performing drag-and-drop tasks is also a bit slower while walking. One study had participants perform drag-and-drop operations; mean completion time was ~40 s sitting vs. ~44 s walking (≈10% slower)[26]. Similarly, point-and-click tasks took a couple seconds longer on the treadmill[26]. These are small absolute differences, but they reflect the general trend: any task requiring precise hand-eye coordination (mouse pointing, spreadsheet cell selection, etc.) can be slightly hindered by walking. The likely reason is the subtle body sway or need to stabilize hands while in motion. Notably, standing desks don’t show this effect – since standing is static, mouse and keyboard performance remains on par with sitting in most studies[27]. Thus, the act of moving (even slowly) introduces a mild performance cost for fine motor tasks.

- Writing, Coding and Data Entry: Direct studies on programming or heavy text composition are sparse, but by analogy, these involve continuous typing and cognitive processing. We can infer that raw coding speed (lines of code per hour) might initially dip on a treadmill desk due to the typing slowdown. However, any increase in cognitive errors (like programming bugs) is not evident – cognitive function isn’t impaired (discussed below). In practice, developers and writers report that after an adjustment period, they can code or write effectively while walking, using the same strategies as for typing accuracy (e.g. lower speeds, frequent brief pauses to think then resume walking, etc.). No study to date has measured code quality or similar knowledge-work output on treadmill vs. seated desks, representing a research gap. Data entry tasks (numerical or form entry) would likely mirror the typing findings: slightly slower input at first, but no loss of accuracy. One field study where employees used treadmill desks for several months found no performance complaints once they got used to it – work quantity and quality remained stable[6].

- Task Completion Times: For general computer tasks (reading and responding to emails, filling out forms, etc.), any increase in completion time tends to be small. A controlled trial measuring a set of simulated office tasks found overall task performance time was ~6–11% longer when walking versus sitting[28]. For example, solving simple math problems on a GRE test took longer on the treadmill (scores ~7 percentage points lower, presumably due to taking more time)[1]. Reading comprehension tasks, however, showed no difference in speed or score between sitting and walking[3] – indicating that for tasks heavy in cognition but light in motor input (like reading or mentally calculating), a slow walk doesn’t slow the user down.

- Long-Term Productivity: Crucially, longitudinal studies indicate that any initial losses in typing speed or task efficiency disappear with practice. Workers adapt to the dual task of walking-while-working over time. In a 1-year trial at a company (36 employees who got treadmill desks installed), researchers tracked performance evaluations and objective metrics and found no significant change in work performance over the year compared to baseline[4][29]. In other words, after an adjustment period, employees were just as productive as before, even though they were walking a good portion of their day. Likewise, a systematic review in 2018 noted that across multiple interventions lasting 3–12 months, no productivity decrements were observed – if anything, some participants reported gains in concentration and efficiency[5]. This aligns with qualitative findings: experienced treadmill desk users often say it’s “second nature” after a while, and some feel more productive due to higher alertness (especially in the post-lunch dip)[7].

- Standing Desks and Comparators: It’s helpful to compare walking vs. just standing. Standing desks, while great for breaking sedentary time, have minimal effect on performance – positive or negative. A review found strong evidence that simply standing does not change work output[27]. The consensus is that standing = sitting in terms of typing speed and cognitive performance, except that prolonged standing might introduce discomfort over many hours. Desk bikes (pedal stations) introduce movement like treadmills do, but primarily involve the legs. Some studies suggest that slow pedaling interferes even less with hand tasks than walking does. In one direct comparison, typing speed dropped about 16% with treadmill walking but only ~6% with cycling[2]. However, other research (e.g. a 137-person trial) reported no statistically significant differences between cycling and treadmill desks on any typing or cognitive outcome[13] – implying that both modes, if done at light intensity, are comparable. For practical purposes, treadmill vs. bike might come down to personal comfort (some find it easier to walk and type than to pedal and type). Both are viable for maintaining productivity, with perhaps a slight edge to cycling in preserving typing speed according to the meta-analysis[2].

Bottom Line – Performance: Expect an initial modest drop in speed on certain tasks when introducing treadmill desks (typing ~5–15% slower, mouse actions a few seconds longer). Plan for a learning curve of a few days to a few weeks; during this time, employees might reserve their most typing-heavy or precision-critical tasks for when they are seated until they feel confident on the treadmill. Crucially, accuracy and quality of work are maintained during walking, as multiple studies show no rise in errors or mistake rates[3][2]. With sensible use (low speeds, good ergonomics) and adaptation, treadmill desks “do not appear to decrease workplace performance”[5]. In fact, once acclimated, many users work nearly as fast as sitting, buoyed by the added alertness that light activity provides.

Effects on Cognitive Function: Attention, Memory, and Executive Control

A key question for knowledge work is whether walking impairs the brain’s cognitive abilities – the concern that multitasking (walking + thinking) might overwhelm people. The evidence here is largely reassuring: walking at gentle speeds has minimal impact on brain function for most standard cognitive tasks. Some aspects of cognition even show slight improvement with activity. Here we break down findings on attention, working memory, executive functions, and related measures:

- Attention and Processing Speed: Simple attention and vigilance tasks (e.g. reaction time tests, Stroop color-word tests, visual alertness tasks) show no decline while walking. For example, John et al. (2009) tested selective attention using a computerized test and found no significant differences between sitting vs. walking conditions[30]. Participants’ ability to respond to stimuli and their mental processing speed were essentially unchanged by walking. This has been confirmed in other studies: a 2015 randomized trial had people perform the Eriksen flanker task (which measures attentional control and interference processing) either sitting or walking at 1.5 mph – and found no differences in reaction times or accuracy between the two groups[31]. The authors concluded that “cognitive control performance remains relatively unaffected during slow treadmill walking relative to sitting.”[9]. Similarly, no change in Stroop test performance has been observed. In practical terms, this means your ability to concentrate on a screen, pay attention to details, or maintain vigilance (like monitoring incoming emails or data) is not hurt by the act of walking. One reason is that walking at a low, regular pace becomes almost automatic (low cognitive load), so it doesn’t significantly divert mental resources from your primary task[32].

- Working Memory and Executive Function: Executive functions include things like updating working memory, inhibiting distractions, and task-switching. Studies have used n-back tasks, go/no-go tasks, and math problems to probe these while on treadmill desks. The general finding: no major impairment, and sometimes a benefit. For instance, one experiment looked at cognitive control (measured via conflict adaptation in a flanker task and response inhibition in a go/no-go) and found walking had no negative effect on these higher-order processes[31]. Both walkers and sitters adapted to high-conflict trials and managed errors similarly, indicating intact executive function while walking. Another crossover study (Alderman et al., 2014) reported that for relatively simple cognitive tasks, participants did just as well walking as sitting[32]. In fact, a comprehensive 2020 study with 137 young adults found that participants actually had better attention and cognitive flexibility scores during the active workstation session than during sitting[33]. (However, the authors noted this could partly be a practice effect since the active session came second, though alternate test forms were used.) Some research even suggests mild physical activity can improve certain executive functions via increased arousal and blood flow. The Mayo Clinic conducted a study where they observed improved reasoning and cognitive scores when people were standing or stepping compared to prolonged sitting[34]. Though that involved some stepping in place, it aligns with the idea that a lightly active body can sharpen the mind.

- Memory (Short-term Recall): The impact of treadmill walking on memory tasks is a bit mixed and may depend on the timing of the task. When people try to memorize or recall information while walking, results vary: verbal memory recall (like remembering words from a list) might see a slight dip during walking in some cases[13]. The large 2020 BYU study noted a slight decrease in verbal memory performance on a word recall test when participants were walking vs. sitting[13]. This could be because the encoding or retrieval of words is a bit disrupted by the dual task of movement. However, other studies have found no significant memory impairment. Notably, there appears to be a “delayed effect” benefit: after walking on a treadmill desk and then stopping, people’s memory performance can improve. Labonté-LeMoyne et al. (2015) discovered that using a treadmill desk had a beneficial effect on attention and memory shortly after the walking period – participants actually did better on recall tests after walking, compared to when they had been sedentary[12]. This suggests that while walking, your memory isn’t worse (and may be roughly the same), and once you sit down you might even experience an uptick in mental clarity and recall, thanks to the prior movement. One meta-analysis found a moderate improvement in recall ability (SMD ≈ +0.68) with active workstations[35], highlighting that mild exercise can enhance certain memory processes (possibly via increased hippocampal engagement or neurotransmitters associated with exercise). It’s worth noting these memory tests are often verbal or short-term memory; other types like spatial memory have not shown deficits either[36].

- Complex Reasoning and Multi-tasking: When tasks become more complex (e.g. solving novel problems, heavy multi-tasking), results are still generally neutral. A pilot study found no change in an advanced multi-tasking cognitive test when using a treadmill or standing desk compared to sitting[34]. That said, if a task is extremely cognitively demanding and also requires intense concentration, individuals might subjectively prefer to stop walking momentarily. The ability to step off or pause the treadmill for a quick period of deep focus is sometimes reported anecdotally. But overall, there is little evidence of cognitive overload at walking speeds around 1–2 km/h. One reason is that such slow walking uses minimal attentional capacity – it’s not like trying to run and do math; it’s more akin to the way people can chew gum and walk. The brain can handle a routine motor task and a mental task concurrently in this scenario.

- Overall Cognitive Impact: Summarizing numerous studies, an authoritative systematic review in 2018 concluded: “Most studies reported cognitive performance was not impaired by active workstations.” Some did note small performance decreases on treadmill/cycling desks, but many lacked statistical power and the effects were not consistent[37][5]. The consensus was that treadmill desks do not meaningfully hurt cognitive function, and in some domains (like executive control or post-activity memory) they might confer slight benefits. Another review stated that active workstations can reduce sedentary time “while having a positive influence on psychological well-being with little impact on work performance”[38]. The American Heart Association reported similarly that active workstations improved certain cognitive tasks in their trials, suggesting these interventions can be introduced “without work performance impairment”[39].

In practical terms, employees can engage in typical knowledge tasks – reading, writing, analyzing data, participating in virtual meetings – on a treadmill desk with confidence that their core cognitive faculties (attention span, comprehension, decision-making) will remain intact. Some employers have even observed better focus in meetings when staff are on treadmills or standing, likely because the slight movement keeps people more alert than passive sitting (preventing the post-lunch slump). One qualitative study of work-from-home treadmill desk users found that many reported “better focus” and felt more attentive in their tasks when walking[7]. Of course, if a task demands 100% undivided attention (like an intense calculation or reading fine print), an individual might choose to pause walking briefly – but that’s at their discretion.

Finally, it’s important to mention neurodiversity: Some individuals with ADHD or similar profiles may benefit even more from treadmill desks. Movement can serve as a “fidget” outlet that actually improves concentration for them. While formal studies are scarce, anecdotal reports and some expert opinions suggest under-desk treadmills might help manage attention in ADHD by providing a constant low-level physical activity (there are even popular articles about under-desk treadmills for ADHD focus support[40]). This could be a fruitful area for future research.

Creativity and Innovation: Does Walking Spark Creative Work?

A popular idea (and often a selling point of active workstations) is that walking can boost creativity. This stems from psychology research showing that physical movement – especially walking – tends to enhance divergent thinking, which is the ability to generate new ideas. We examine how this plays out in the office context:

- Walking and Creative Thinking: The landmark study by Oppezzo & Schwartz (2014) demonstrated that walking has a powerful positive effect on creative idea generation[14]. In their experiments, participants came up with ~60–80% more novel uses for everyday objects when walking (on a treadmill or outdoors) compared to sitting[14]. Walking “opened up the free flow of ideas” and even after sitting back down post-walk, the creative boost persisted for a while[16]. Notably, this effect was strongest for divergent thinking tasks (like the Alternate Uses Test where you list creative uses for a brick), and less so for convergent creativity (like solving a single insight problem – walking helped only a small subset of people on those)[41]. Outdoor walking gave the biggest benefit, implying both movement and environment play roles[42]. The takeaway: a short walk can be an excellent creativity booster, which suggests treadmill desks might facilitate more creative brainstorming during work.

- Treadmill Desk vs. Walking Break: The critical distinction is between walking while working on a creative task versus taking a break to walk and then working. The Oppezzo study let people walk without doing another task, focusing solely on creativity prompts. In the office, one might try to do creative writing or design work while actively on the treadmill. Does simultaneous walking help creativity? Recent evidence indicates not significantly. A 2020 controlled study specifically tested creative performance during treadmill desk use: 12 participants completed classic creativity tests (verbal and written Alternate Uses and the Remote Associates Test) twice – once seated at a desk, once walking at 1.5 mph on a treadmill desk[43][44]. The results showed no significant differences in creativity scores between sitting and walking conditions[15]. Neither divergent thinking (Alternate Uses scores) nor convergent insight (RAT scores) improved with concurrent walking[15]. In other words, walking at the same time as performing the creative task did not boost output – but importantly, it didn’t hurt it either. This suggests that any benefit of movement on creativity might require either a higher walking intensity (a leisurely stroll outdoors) or a non-dual-task context (focus on ideation during the walk). In a treadmill desk, because your attention is partly on typing or sketching, you might not tap into the full creative boost that free walking provides.

- Alternate Uses & Brainstorming: Some companies encourage employees to take walking meetings or brainstorming strolls, precisely to enhance creativity. If an employee is trying to think of innovative solutions, a walking break might be more effective than attempting to brainstorm while seated. The treadmill desk can still be part of this process – for example, one could hop on the treadmill at a low speed while on a call to discuss ideas (the physical motion could stimulate thinking without needing to write at that moment). After the walk, when it’s time to formally write down or implement the ideas, they can do so either while still walking or sitting, with the creative impetus already sparked. The key is that movement is beneficial for idea generation, but combining movement and execution of creative work needs to be balanced. Some creative professionals report that doing rote tasks (answering emails, etc.) while walking is fine, but for deep creative thinking they might take a break from typing. This aligns with the science: walking improves divergent idea generation in real-time[14], but treadmill walking during complex creation might just maintain baseline performance[15].

- Standing vs. Walking for Creativity: There’s also an interesting point that even standing can modestly impact cognition. A study on “embodied cognition” found that simply standing (vs. sitting) led to improved creative problem solving, hypothesizing that a more active posture might encourage mental flexibility[45]. However, the evidence is not as robust as for walking. One media article humorously noted an office that had an “idea while on your feet” culture. The treadmill desk goes further by actually keeping you moving. The movement seems to be key for divergent thinking – the mild exercise effect likely increases arousal and brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF), which can facilitate cognitive processes.

Bottom Line – Creativity: Walking is a known creativity enhancer, so leveraging treadmill desks for tasks like brainstorming is a promising idea, with some caveats. For generating ideas (many alternatives, loose thinking), encourage use of treadmill or walking breaks – e.g. an employee might walk in place while voice-recording ideas or using a speech-to-text brainstorm app. However, for tasks requiring concentration on creative production (like writing a complex report or coding a novel solution), the treadmill won’t magically make one more creative in that moment, though it also won’t impede the creative process beyond the minor effects on typing. Many find the best approach is to use walking to overcome creative blocks and then alternate to sitting or standing when refining those ideas.

It’s also worth noting that creative benefits of walking apply to all employees – not just traditionally “creative” roles. Problem-solving in any job can benefit from a fresh perspective. A treadmill desk gives the option to pace during tough problems. As one qualitative study participant put it, using the treadmill desk made them feel more mentally “engaged” and even “improved creativity” on the job[7] (this was self-reported, but echoes many users’ anecdotal experiences).

Adaptation Over Time and Training Effects

When first introducing treadmill desks, employees may experience novelty and some difficulty coordinating tasks. Research indicates a learning curve whereby cognitive-motor interference diminishes with practice:

- Initial Phase: The first few sessions of walking while working can feel awkward. Users might need to look at the keyboard more, or they may notice a slight drop in their typing or reading pace. Studies without any acclimation period (immediate testing) show the strongest performance differences[46]. For example, in one lab study participants had no prior practice on the treadmill condition and showed the 6–11% performance decrements noted earlier[47]. This likely represents the worst-case scenario. The authors of that study and others hypothesized that an acclimation period could mitigate the declines[48].

- Evidence of Adaptation: Indeed, research that incorporated training finds smaller (or no) differences. Thompson & Levine (2011) reported that when employees were allowed to train on a treadmill desk over time, their typing performance eventually was not significantly different from sitting[21]. Similarly, Funk et al. (2012) found that after practicing, individuals could type at around 92–95% of their seated speed while walking, especially at lower speeds[21]. Essentially, people learn to compensate – e.g. they develop a steadier gait or improve their hand-eye coordination on the move. The body adjusts to the dual task.

- Long-term Studies: By six months to a year into use, studies show no performance loss. The 12-month trial by Levine’s Mayo Clinic team found work output was sustained or even subjectively improved, with participants reporting no issues after the initial novelty wore off[4][29]. In qualitative interviews, some users noted it took “a few weeks” to feel completely natural working while walking, but after that they didn’t feel any hindrance – it became just another way of working. We can analogize this to something like using a standing desk: at first one might fatigue or fidget, but then one finds a comfortable way to stand and work. With treadmill desks, adaptation involves finding the right speed and rhythm where one can walk unconsciously and focus on work.

- Motor Learning: The adaptation is partly motor learning – your brain learns to fine-tune leg movements so they don’t disturb your hands. Research in motor control suggests that when doing two tasks together repeatedly, people learn to “decouple” them better. In treadmill desk users, observers often note that they develop a very smooth, almost gliding walk when typing, minimizing upper body sway. In contrast, a new user might bounce more, causing more difficulty. So training literally changes the gait to be more compatible with desk work.

- Psychological Adaptation: There’s also a psychological aspect: initially workers might feel self-conscious or distracted by the novelty (“I’m walking while emailing – this is odd!”). Over time, the treadmill fades into the background of their mind. A qualitative study during the COVID-19 work-from-home period found that after some use, people incorporated treadmill desks naturally into their workflow for certain tasks, and reported the main barriers were not performance but things like call etiquette or setup issues[49][50]. Many described it as a “game changer” once they got used to it, improving their daily routine without hurting work quality[7].

- Recommended Onboarding: To harness adaptation, companies should implement an onboarding program: start with short durations (15 minutes a few times a day) and simple tasks until employees gain confidence. Perhaps begin with reading or viewing tasks on the treadmill (which are easier) before multi-tasking with typing. Provide guidance on speed (start at ~1 km/h and adjust gradually). By week 2 or 3, many will be comfortable doing most tasks while walking. Encourage them to stick with it through the initial learning period – as evidence shows initial performance dips are temporary[22].

- Adjustment of Expectations: Managers should be aware that you wouldn’t introduce treadmill desks on Monday and expect 100% normal output on Tuesday. A short adjustment period is normal. However, given that productivity was unchanged at 6 and 12 months in controlled studies[17][4], any upfront time cost is an investment quickly repaid by health and engagement benefits (and possibly regained productivity as alertness improves).

In summary, adaptation over time is real and important. This means concerns about minor slowdowns should be weighed against the fact that they diminish with continued use. By a month or so in, employees often perform at or near their usual capacity while walking. Companies could consider a trial period where expectations are managed, after which employees and managers can evaluate if any productivity impact remains (most data says it won’t, for low-speed walking). As one systematic review put it: treadmill desk users may experience “modest, short-term decreases in motor performance, but cognitive performance and long-term work performance are not negatively affected”[51]. That statement encapsulates the adaptation phenomenon well – short-term motor skill adjustment, long-term no harm.

Moderating Factors: Task Type, User Characteristics, and Ergonomics

Not all work and workers are the same. Various factors can moderate how walking affects performance:

- Task Complexity: The more complex or high-stakes the task, the more caution is advised when pairing with walking. Routine tasks (data entry, responding to emails, file sorting) are very amenable to treadmill desking – many people find they can do these on “autopilot” while moving. Complex tasks (e.g. intense financial analysis, writing dense code, designing a critical presentation) might be better done in intervals – walking during parts of the task that are rote or brainstorming-oriented, and standing/sitting during parts that require absolute precision or deep concentration. That said, as we saw, objective cognitive tests show even complex mental tasks aren’t significantly impaired. It may boil down to user comfort: some individuals might feel any movement distracts them during a really complex thinking session, whereas others feel it helps them focus. Personalization is key.

- Multitasking & Distractions: If an employee must multitask heavily (e.g. talk on the phone, take notes, and browse data all at once), adding walking is a third task – albeit a low-level one. Studies on dual-tasking find that if both tasks demand high attention, performance suffers. Here, one task (walking) is low attention, so it usually doesn’t cause issues. But if someone is already juggling many tasks, they should be careful not to push themselves into cognitive overload. It might be wise to avoid treadmill use during tasks that are inherently high cognitive load plus high motor load (for example, manually dialing into a video conference while mentally preparing a presentation – maybe do one thing at a time). Most normal work multitasking (typing while maybe listening to music, etc.) is fine on a treadmill as long as the speed is slow.

- Ergonomics (Keyboard & Monitor Position): Proper ergonomics are crucial. A badly arranged treadmill desk could cause more performance issues (and physical strain) than the walking itself. The desk height should be adjusted so that the keyboard is at roughly elbow height and the monitor at eye level. If the monitor is wobbly or the desk surface shakes, it will be harder to focus and click accurately. Quality treadmill desk setups have stable surfaces that don’t vibrate much as you walk. An external keyboard and mouse positioned correctly can help maintain normal typing posture. If the keyboard is too high/low or too far, the user might have to look down or reach, exacerbating any coordination difficulty. Many performance studies ensured participants had a properly adjusted station; doing so in the workplace is equally important to preserve productivity and prevent neck/wrist strain.

- Footwear: Walking all day in dress shoes or heels is not advisable. Comfortable, supportive shoes (or even walking barefoot/socks if appropriate and safe) help reduce fatigue and improve gait. Users wearing inappropriate footwear might alter their gait or experience discomfort that distracts them. Some companies that implemented treadmill desks recommend having a pair of walking shoes at one’s desk. If an employee is in a setting where athletic shoes aren’t dress-code acceptable, even a soft-soled loafer is better than hard heels. This is both a productivity and a safety consideration.

- Fitness Level: Individual fitness and balance can influence initial adaptation. Someone who isn’t used to any walking might fatigue faster or find coordination harder at first. However, treadmill desk walking is very low intensity (usually <2 METs). Even relatively unfit individuals can physically handle it; they just might need to start with shorter bouts (5–10 minutes and building up). Fitter individuals often take to it quickly and can handle longer durations. Over time, fitness can improve from using the treadmill desk, which in turn might make it even easier to use – a positive feedback loop. We did not find evidence that age or baseline fitness materially change cognitive effects; older workers can successfully use treadmill desks, though they should be extra careful about balance (using handrails initially if needed, and ensuring speed is kept low).

- Age: Most studies were on younger adults, but a few included middle-aged office workers. There’s no indication that age differences (20s vs 50s, for example) lead to different cognitive outcomes; however, older individuals might have a longer adaptation period and should be monitored for any balance issues or joint pain. For older workers with musculoskeletal concerns, alternating sitting, standing, and walking is recommended rather than continuous walking.

- Sex/Gender: No significant gender differences in performance have been reported. Men and women in studies generally showed similar patterns of typing changes and cognitive results. Any minor differences usually trace back to individual typing skill or fitness rather than gender per se.

- Body Weight: Heavier individuals (especially those not accustomed to exercise) might initially find treadmill walking more tiring, which could affect endurance. But treadmill desks are specifically touted as a way to help overweight/obese employees integrate activity at work. In Levine’s 1-year trial, participants ranged from lean to obese and all managed the transition, with obese participants actually losing the most weight and reporting positive outcomes[17][52]. Treadmill weight capacity should be considered (most office treadmills support at least 110–150 kg, but manual models might differ). There’s no direct evidence that obesity impairs cognitive performance on a treadmill desk; if anything, the health benefits could help cognitive function long-term (e.g. better glucose control helps brain function).

- Neurodiversity: Mentioned earlier, conditions like ADHD might moderate the effects in a beneficial way. An ADHD individual might concentrate better while walking (some small-scale reports support this), whereas a neurotypical individual might see no difference. On the other hand, someone on the autism spectrum with sensory sensitivities could potentially find the sensation or noise of the treadmill distracting. These personal factors mean employers should allow an element of choice – not everyone must use a treadmill desk; those who prefer static workstations can keep them, ensuring an inclusive approach.

- Noise and Office Environment: Noise from the treadmill or footsteps can be a factor in shared environments. While many treadmill desks are designed to be quiet, there is a motor hum and the sound of footfalls. If an office is silent, this might be noticeable and could distract coworkers (or the user, if they are noise-sensitive). This can moderate effectiveness: in a noisy environment (open office with lots of background chatter), a treadmill’s noise is negligible; in a silent library-like office, a treadmill might be intrusive. Solutions include placing treadmill desks in designated areas or using models known for low noise levels (~45 dB or so, about the level of a quiet conversation)[53]. One advantage of manual treadmills is they have no motor noise – only the sound of the belt and footsteps. Many users describe this as a soft swishing that fades into the background. In contrast, an electric treadmill has a constant motor whir. If noise is a concern, this could tip preference towards high-quality manual treadmills. Additionally, using a rubber mat under the treadmill can reduce vibration noise.

- Manual vs. Electric Treadmill Differences: Though research hasn’t directly compared cognitive or performance outcomes on manual vs. motorized treadmills, there are some theoretical differences:

- Manual (self-paced) treadmills require the user to propel the belt. This can mean a slightly higher exertion at the same speed, and possibly more variability in speed if the user’s pace fluctuates. Some manual models (especially curved treadmills) have more friction at startup, which might cause a tiny initial jolt when getting on. Users often acclimate to keeping them moving smoothly. The advantage is that speed changes are intuitive – speed up your steps to go faster, or slow down and it will stop. This could be cognitively simpler than reaching for controls on an electric model, thus less disruptive when transitioning on/off or adjusting speed. Manuals are also almost silent (no motor), which can improve the experience for both user and coworkers. Stride smoothness might differ: electric treadmills force a constant belt speed, which could actually cause more upper-body sway if one’s steps don’t naturally match (you might find yourself bobbing slightly if you’re subconsciously fighting the belt speed). A manual treadmill moves exactly as you move, potentially leading to a very natural gait – as long as it’s well-designed to avoid stickiness. On the downside, a cheap manual treadmill with poor bearings could increase friction and make walking uneven, which certainly would not help productivity. High-end manual treadmills are built to provide smooth low-friction motion and often have a slight incline to aid belt movement.

- Electric treadmills offer precise speed control and typically a very even motion at constant speed. Users can set, say, 1.0 mph and trust it will stay there. This can be good for consistency but requires using a console or remote. From a cognitive standpoint, adjusting a manual treadmill is more intuitive (just walk a bit faster/slower) whereas adjusting an electric one involves pressing a button – a minor thing, but if one frequently changes speed (e.g. speeds up during reading, slows when typing), the manual might integrate better. Electric models also produce motor and fan noise, ~50–70 dB depending on design and speed[54]. At low speeds, many office treadmills are fairly quiet (~whisper level), but the motor is continuous even if you pause walking (unless you pause the machine). Some users report the white noise hum can even be soothing, while others might find it annoying. So individual preference plays a role.

Given these differences, an employee doing tasks requiring a lot of stop-start (e.g. frequent interruptions) might prefer a manual treadmill which stops immediately when they step off (no need to hit a stop button and wait for it to slow). Conversely, someone who wants a perfectly constant pace for hours might lean toward electric. No study so far has isolated whether any performance metrics differ between the two types; it’s likely the differences are more about comfort and noise.

- Task Equipment (Typing on laptop vs. desktop): One more factor: typing on a firm desktop keyboard vs. a laptop’s built-in keyboard can change the experience. Many find that a stable external keyboard is easier to use on a treadmill desk (less screen bounce from key presses). If someone tries to use a lightweight laptop on a treadmill desk without securing it, the act of typing can jiggle the screen a bit in time with steps – an external monitor or docking setup solves this. So providing the right equipment (monitor arms, etc.) moderates the success of implementation.