Breathing is the essence of life. With every breath, humans inhale around half a litre of air, which mainly fuels the energy production of every single cell. Generally speaking, there are only two main states in which we are reminded just how important breathing is to us.

First, in a very pleasant setting, when deeply breathing in fresh air, for example in an inspiring environment in the middle of nature or while performing yoga or meditation. The immediate and measurable calming effect on the body can have a profound impact and truly demonstrates the power of our lungs and interconnection they have to the rest of our bodies.

Second, in a very unpleasant setting, when we suddenly feel as though we can’t breathe as we are used to. This is a state that can quickly turn into a life threatening fight for survival and cause uncomfortable arousal.

There is a state in between these two extremes – one which we don’t tend to notice because we have gotten so used to it. This is the effect that sitting has on our lungs. While not killing us right away, the long-term effects on our health are outright scary.

It's not uncommon for the average office worker to spend several hours a day in a position in which he or she slumps over a desk with hunched shoulders and a rounded spine. For many, this is a daily norm. While we have become perfectly used to this, and might even appreciate the apparent comfort that comes from this low effort posture, for the lungs it is a highly unnatural state that results in a substantial reduction in oxygen volume.

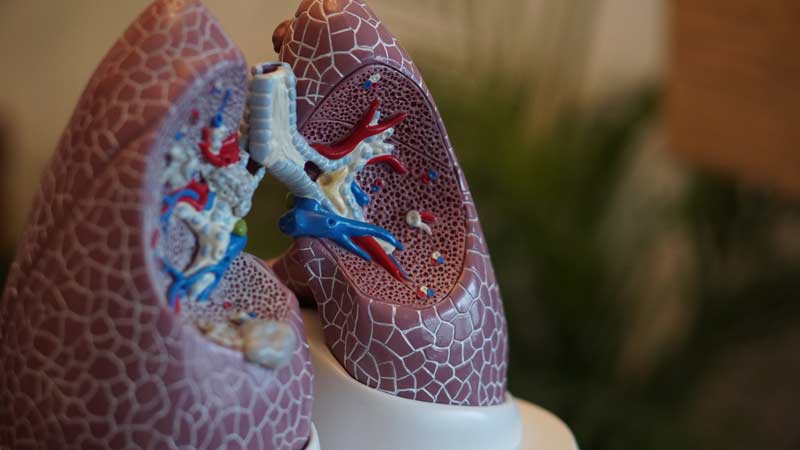

To understand the whole picture of compression caused by poor posture, it is essential to understand how our lungs work. The lungs are basically just a tissue in which the exchange of air is taking place. Lungs don’t have the function to contract or expand by themselves, they just follow the movements of the muscles that surround them. First and foremost, the lungs inflate due to the compression of the underlying diaphragm muscles, which separate the lungs from the lower part of our upper body that contains our stomach and intestines. Breathing primarily happens by moving this layer of muscles down, with the lungs passively following. Only after this first motion do our lungs expand with our rib cage and we inhale fresh air. This second mechanism typically requires intentional action; for example, when engaging in physical exercise we require a greater oxygen intake. In the described typical sedentary posture, the abdominal compartment below the diaphragm is compressed between the upper body and the flexed hip. In this state, our primary breathing mechanism becomes chronically impaired, with the involved muscles losing strength over time. This can lead to something we will get to know shortly as superficial breathing (Landers et al., 2003; Crosbie & Myles, 1985).

While most of us have become used to the diminished lung capacity fostered by poor posture and hardly notice any real difference in our breathing while sitting, some individuals are acutely aware of how posture affects their breath. In a study that looked at the effects of different postures on breathing in brass instrument players, simply sitting down reduced activity in the muscles of the abdominal wall by 32-44% compared to standing. Even sitting on a downward sloping seat led to an 11% reduction in the maximum duration of a note played on a trumpet (Price et al., 2014).

While most of us do not need to worry about holding a note while playing a wind instrument, that does not make us immune to the negative effects of sitting when it comes to our respiratory function. In a study involving 70 able-bodied volunteers, researchers looked at how four different seating positions influenced breathing and lumbar lordosis (the inward curvature of our lower spinal cord). Compared to standing, seated positions were overall worse for lung capacity and expiratory flow, as well as lumbar lordosis. The worst position, associated with significant decreases across all measures, was a slumped posture where the pelvis was positioned in the middle of the seat as the volunteer leaned against a back-rest (Lin et al., 2006). This is exactly the position associated with the typical desk setting.

So why is all this a problem for us? As reduced respiratory function further compromises muscle activity, and as impaired muscle function negatively impacts breathing, this creates something of a vicious circle leading to shallow breathing patterns becoming the norm (Wirth et al., 2014). Taking shallower breaths means less oxygen is delivered to the body’s tissue, which compromises cellular metabolism and muscle function, and can lead to decreased stamina and energy.

A lack of oxygen also affects brain activity, and can lead to poor concentration, impaired focus and reduced memory. A reduction in expiratory flow also means that the body is less able to dispel waste gases, including carbon dioxide.

Poorer respiratory function has also been associated with increased levels of stress hormones, whereas deeper, fuller breaths appear to have a calming effect on both the mind and the body. In one study, healthy volunteers who received training in diaphragmatic breathing showed improvements in sustained attention, as well as lower levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) after 20 sessions over eight weeks (Ma et al., 2017).

In recent years, medical research has revealed even more profound impacts on long-term health, specifically the increased risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke (Hancox et al., 2007). This is likely caused by a dysfunction in the smaller blood vessels of the brain when lung capacity is compromised, resulting in a permanently low level inflammatory state. Evidence for this link has been seen in a longitudinal study that assessed respiratory function and cerebral small-vessel disease in women over a period of 26 years. The researchers found that lower scores on two measures of lung function spanning a time frame of 20 years were associated with a higher prevalence and severity of brain lesions and the most common type of stroke (Guo et al., 2006). Other studies looking at respiratory function and cerebrovascular disease have found similar associations, which suggests that improving lung capacity may have a protective effect against stroke in later life (Liao et al., 1999).

Today we are learning that, in addition to being a symptom of cardiovascular disease itself, a chronic shallow breathing pattern may be an independent risk factor for poor cardiovascular health. This association was first noted in the Framingham study, which followed 5,200 individuals over three decades (Sorlie et al., 1989; Ashley et al., 1975) and has been recently followed up in research from Korea, corroborating the idea that improved respiratory function may help decrease a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease down the line (Kang et al., 2015).

About the Author

Eric Soehngen, M.D., Ph.D. is a German physician and specialist in Internal Medicine. With his company Walkolution, he battles the negative health effects that sitting has on the human body.

Eric Soehngen, M.D., Ph.D. is a German physician and specialist in Internal Medicine. With his company Walkolution, he battles the negative health effects that sitting has on the human body.

Walkolution develops ergonomically optimized treadmill desks, which help to bring more movement into the daily work routine in the office or home office.

Photo credit: Deb Kennedy